Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman is arguably the world’s leading authority on human decision-making and cognitive biases that exist due to irrational judgement. As part of his research on the mind, he created a list of the five variables that lead to suboptimal decision-making as follows:

- A complex problem

- Incomplete and changing information

- Changing and competing goals

- High stress, high stakes involved

- Must interact with others to make decisions

Investing involves all five of these variables, making it extremely difficult to consistently make high-quality decisions. Furthermore, the more decisions that we force ourselves to make in investing the more likely we are to make the suboptimal decisions that will lead to underperformance. This idea that the more decisions you have to make increases the likelihood that poor decisions will be made is referred to as decision fatigue.

Have you ever been on a diet and after a number of days of focusing on what you are eating you cave in to an eating binge that wipes out all of the progress you had previously made? Have you ever gone to the grocery store and shopped all of the sale items only to cave in and buy candy bars at the cash register upon check-out? These are all examples of how decision fatigue can cause you to act against your better judgement in everyday life.

What are other examples of cognitive biases?

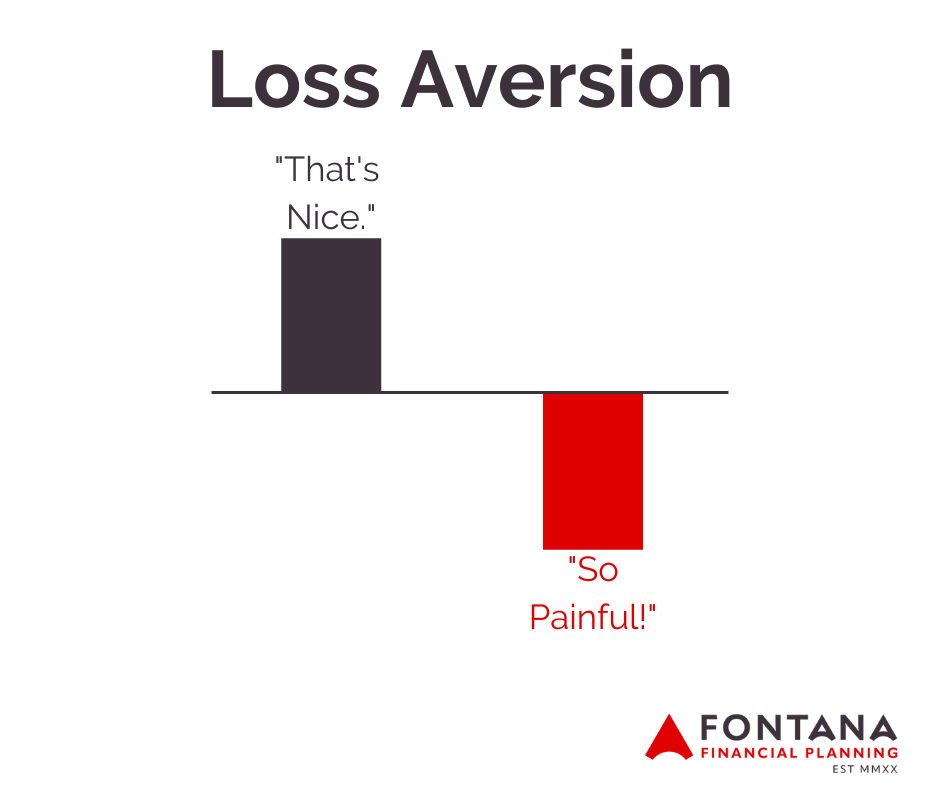

Loss Aversion

Loss aversion is the tendency to want to avoid losses as the pain of a loss is about twice as impactful as the joy of a gain. This bias causes us to feel extreme pain when we see the value of our portfolio go down and subsequently to make emotional, irrational changes to our portfolio in times of distress.

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is the heuristic that causes us to only seek out information that confirms the opinion that we have instead of the information that challenges our opinion. By seeking out information that supports what we already believe, we are not challenging ourselves to make rational decisions based on the evidence available but instead are simply trying to convince ourself that the preconceived belief that we already held must be true.

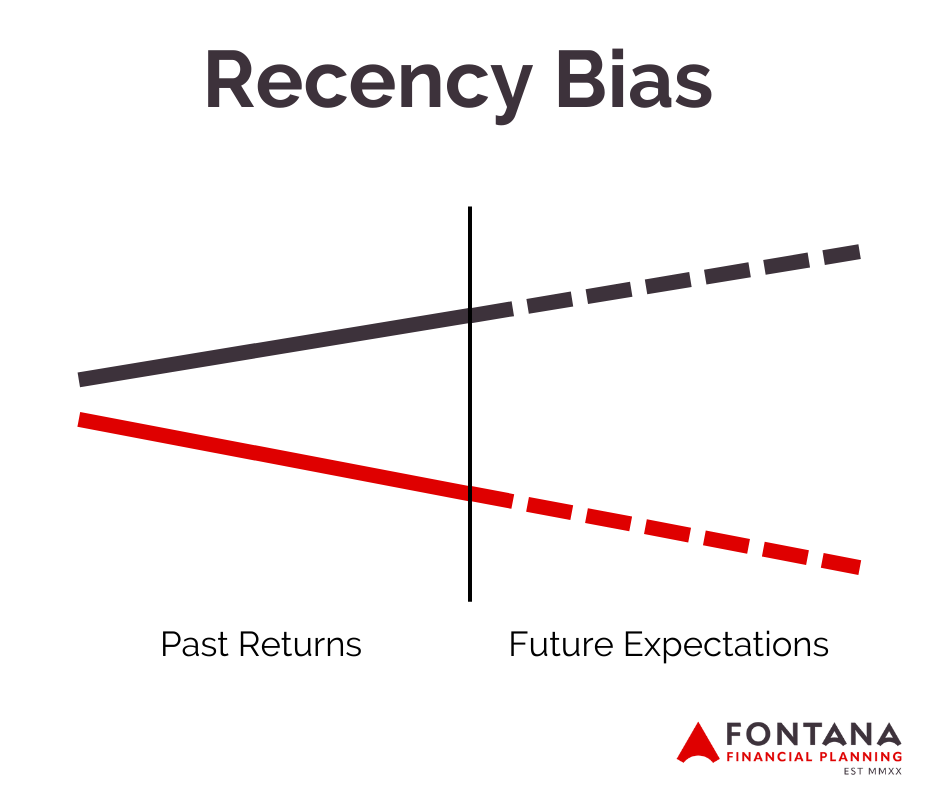

Recency Bias

Recency bias leads investors to make decisions based on what has recently occurred in the market. During the tech bubble, as stories of wildly successful IPO’s and double digit returns consistently headlined the evening news investors piled into tech names with no earnings just before the NASDAQ fell nearly 80 percent. This is also what lead investors to sell out near market bottoms in 2009, after losing 50 percent of their wealth, and to sit in cash until markets reached pre-crash highs despite the fact that they most likely would have recouped all losses simply by taking a long-term view and holding their investment or even come out ahead by employing a rebalancing strategy.

Hindsight Bias

Hindsight bias is the tendency to look at past events as predictable despite there having been little to no basis for predicting the event beforehand. Looking back at the great recession, it seems obvious that the housing market was out of control and that a decline in the housing market could have major repercussions across the economy. With the benefit of hindsight, we are able to find the data points that make the thesis seem obvious. That said, that information comes out as part of the noise of information that is made available everyday and if the impending recession were really as obvious as they seemed to be then investors would have easily been able to anticipate what would occur and avoid the losses they likely ended up sustaining.

How do these biases affect investor returns?

Let’s first see how institutional investors are affected. If anyone should be able to overcome behavioral errors, it is institutions comprised of investment professionals with advanced degrees, vast amounts of research at their disposal, and access to exotic investments who spend hours upon hours examining the markets each day, right? Despite all of these advantages compared to the typical retail investor, the average endowment fund is unable to beat a simple 60/40 portfolio as shown by the NACUBO annual study of endowments that reported that the 10 year return for the average pension was 7.5% compared to 9.9% for the 60/40 index portfolio.1

The Federal Reserve performed a study where they analyzed mutual fund investor inflows and outflows from 1984 to 2012 and compared the results to a simple buy and hold strategy over seven year periods. They found that investors tended to pour money into mutual funds following periods of outperformance (buying high) and pulled money from the funds after sustaining losses (selling low). When comparing the return-chasing tendencies that investors showed to the performance they would have achieved by simply buying and holding over seven year periods they found that investors lagged by up to 5 percent per year or as much as 40 percent over a seven year period.

Investment research firm DALBAR ran a similar study where they compared dollar-weighted returns of mutual funds to the index and found that the average equity fund investor trails the S&P 500 by nearly 3 percent per annum. The results are even more staggering on the fixed income side, where the average investor trails the index by nearly 4.5 percent.

What is an investor to do?

According to a Vanguard study titled Advisor’s Alpha, the mutual fund company estimates that on average having an advisor to provide behavioral coaching adds 150 basis points (1.5%) of additional yield per year. Of course, this will not come all at once but cluster during times of market panic and euphoria.

The key to avoiding falling victim to your biases starts with developing a plan that is systematic, long-term, and rules-based. Through the systemization of your process, you are able to ensure that your biases can’t blind your decision making. In taking a long term approach, you are able to remove decision fatigue and the want to make changes based on day to day changes. By making your process rules-based, you make sure that your decisions are based on fact and not feeling.

According to finance author Ben Carlson in his book A Wealth of Common Sense, a study was done that looked at brokerage account data of individual investors to determine the 10 most important measures of poor investment behavior. They found that by correcting those investor errors that investor returns could be improved by three to four percent.

By developing a process that is rules-based, you are able to take your natural biases out of the equation and simply rely on quantitative evidence for decision making. Billionaire hedge fund manager Joel Greenblatt famously wrote a book titled The Little Book that Beats the Market where he introduced his Magic Formula. This formula screens company financial information to find high quality companies trading for cheap valuations. He ran a study over a two year period where he allowed investors to either invest in all of the companies selected by the Magic Formula or to pick and choose those investments they felt worthy of investment and to disregard those they felt to be undesirable. Those who trusted the screen and bought all stocks returned 84.1 percent while the investors who selected the companies from the screen for which to invest returned 59.4 percent (the market returned 62.7 percent for reference). In this case, human bias took away from the potential return by 23.7 percent over a two year period compared to the systematic, rules-based alternative.

Left to their own devices, investors will fall victim to their own biases even if they are aware of them. While there are many facets of an investor’s financial life that an advisor can help, providing behavioral coaching in times of uncertainty is arguably the most valuable service an advisor can provide.

Check out our other videos: Fontana Financial Planning YouTube

Disclosure: Past performance may not be indicative of future results. Investing involves risk and you may incur a profit or loss regardless of strategy selected, including diversification and asset allocation. The foregoing information has been obtained from sources considered to be reliable, but we do not guarantee that it is accurate or complete, it is not a statement of all available data necessary for making an investment decision, and it does not constitute a recommendation. Any opinions are those of Michael Dunham and not necessarily those of Raymond James. Rebalancing a non-retirement account could be a taxable event that may increase your tax liability.

1Source: Morningstar, 60/40 portfolio consisting of 60% S&P500 TR and 40% Bloomberg Barclay’s Aggregate US Bond Index rebalanced quarterly, 12/1/1980-11/30/2020

The S&P 500 is an unmanaged index of 500 widely held stocks that is generally considered representative of the U.S. stock market. The Bloomberg Barclays US Aggregate Bond Index is a broad-based flagship benchmark that measures the investment grade, US dollar-denominated, fixed-rate taxable bond market. Indices are not available for direct investment. Any investor who attempts to mimic the performance of an index would incur fees and expenses which would reduce returns.